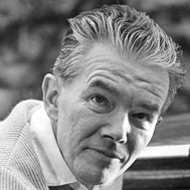

Jan Novák: Musician and humanist

- Eva Nachmilnerová

To mark the 30th anniversary of the death of the composer Jan Novák, the Prague

Spring festival has organised a concert in his honour featuring selected Novák choral

and chamber works.

Jan Novák (8 April 1921 – 17 November 1984) ranks among the most distinct Czech post-

war composers. The fact that his oeuvre is not overly known is in part related to the course his

life took. At the time when he was at the peak of his creative powers, in August 1968 he left

his homeland and went to live in turn in Denmark, Italy and Germany. For an artist who in

the 1960s was in Czechoslovakia an acknowledged composer with a large group of supporters

and friends, departure meant loss of background, performers and listeners alike. He found

himself amidst the Western artistic milieu, where stylistic trends different to those back at

home prevailed.

LIFE AND WORK

Jan Novák was born on 8 April 1921 in Nová Říše in Moravia. In 1933 he enrolled at the

Jesuit Grammar School in Velehrad, which provided a first-class classical education, with

emphasis being placed on languages (in addition to Latin and Greek, Russian, German and

Esperanto were taught there). Yet owing to his transgressing the strict discipline that reigned

at the institution he was expelled. Novák completed his secondary education at the Classical

Grammar School in Brno and subsequently attended the Brno Conservatory, where he studied

composition (with Vilém Petrželka), the piano and conducting. After spending two and

a half years in Germany as a forced labourer, in 1945 he resumed his studies at the Brno

Conservatory and after graduating in 1946 began attending the Academy of Performing Arts

in Prague, where he studied with Pavel Bořkovec, before returning to Brno to enrol at the

newly founded Janáček Academy of Music and Performing Arts.

As a recipient of a scholarship from the Jaroslav Ježek Foundation, from June 1947 to

February 1948 he studied in the USA, first participating in the summer composition master

classes at the Berkshire Music Center in Tanglewood (in the class of Aaron Copland) and

subsequently taking private lessons from Bohuslav Martinů in New York. The criticism

Martinů initially levelled against Novák’s work (highlighting the somewhat awkward

treatment of themes and sloppiness in development of motifs), first acted like a “cold shower”

on the fledgling composer. After recovering from the initial shock, however, he experienced

a learning curve he would never forget, with the time spent with Martinů and their friendship

playing a crucial role in his evolution.

Novák returned to Czechoslovakia in February 1948, at the time of the Communist coup. He

settled in Brno, mainly earning his living by composing music for short and puppet films,

radio and theatre plays, and by giving performances in a piano duo with his wife Eliška

Nováková. His works dating from the 1950s, revealing a distinct Martinů influence, were

symbolically ushered in by the Variations on a Bohuslav Martinů Theme for two pianos

(1949) and its arrangement for orchestra (1959). Attention was also gained by his symphonic

and concertante pieces (e.g. the Oboe Concerto written in 1952).

In the 1960s, Novák further extended his range of genres and compositional means; for a

short time he employed elements of dodecaphony and aleatoricism in his compositions,

first applying the twelve-tone technique as a thematic material in the middle section of his

Capriccio for cello and small orchestra (1958), with the chamber piece Passer Catulli (1962)

being considered one of the apices of this phase. In 1963 he co-founded “Creative Group A”,

made up of Brno-based composers and musicologists. From the end of the 1950s, a vital role

in his creation was played by his penchant for Latin. The original use of the Latin meter while

respecting the proportion between long and short syllables would serve as an impulse for his

entire further work.

A liberal-minded composer who always avowed his artistic and civic opinions, Novák ran

into trouble with the official authorities and the dogmatism of the Czechoslovak Union of

Composers, who with great difficulty tolerated his openness and “commotions”; after in

1961 he refused to participate in the election of lay judges, he was briefly expelled from

the organisation, subordinate to the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. Paradoxically,

however, at that time he received commissions from leading Czech and Slovak film directors

and created music for Karel Kachyňa (Suffering, Coach to Vienna, Night of the Bride, etc.),

Jiří Trnka (The Cybernetic Grandma), Karel Zeman (The Stolen Airship) and Martin Hollý

(Raven’s Road).

Novák’s experience with film and incidental music also manifested itself in the extreme

dramatic forcibility of his cantata Dido (1967) for mezzo-soprano, narrator, male chorus and

orchestra to Book 4 of Virgil’s Aeneid, his paramount work prior to emigration.

The composer perceived with hope the gradual unclamping of the social situation in

Czechoslovakia in the second half of the 1960s. When in August 1968 the Warsaw Pact

forces invaded Czechoslovakia, he was on a tour of Italy with the Kühn Mixed Choir.

Novák decided not to return to his homeland and he, his wife and two little daughters left

via Germany for Aarhus, Denmark. He responded to the tragic events back at home with the

choral cantata to his own Latin lyrics Ignis pro Ioanne Palach (1969); another piece with a

clearly political subtext was his cantata Planctus Troadum written in the same year.

Dating from the time he and his family were about to move to Italy is Mimus magicus for

soprano, clarinet and piano to Virgil’s poetry (1969), which Novák composed to commission

for the competition in Rovereto, where his family subsequently moved. During his time

in Italy (1970–77), Novák mainly created vocal and chamber pieces. Whereas he performed

his choruses to Latin texts with his Voces Latinae choir, the bulk of his chamber works were

written for his daughters, the pianist Dora and the flautist Clara.

In the final phase of his career, following Novák’s departure for Germany, where in 1977 he

and his family settled in Neu Ulm, he composed orchestral works (Ludi symphoniaci, Vernalis

Temporis Symphonia for solos, chorus and orchestra, Symphonia Bipartita) and a number of

pieces for chamber ensemble – Sonata da Chiesa I and II, Sonata solis fidibus for violin and

the piano work Hymni Christiani. In addition to a looser fantasy form and a more extended

structure, these pieces are characterised by a more profound musical expression.

In 1982 the conductor Rafael Kubelík and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and

Chorus performed the cantata Dido in Munich. During his lifetime, however, Novák did not

experience great recognition of his work. On 17 November 1984 he died following a serious

illness. In 1996, President Václav Havel awarded him a state honour in memoriam and in

2011 the composer’s remains were relocated from Rovereto to Brno.

Novák’s relatively extensive oeuvre includes orchestral, chamber and vocal pieces, an opera,

ballets, music for theatre, film and radio plays. The fundamental traits of his musical language

are remarkably constant – a lucid form, a bold rhythmic component with frequent use of

syncopated and ostinato rhythms, sophisticated melodic ideas, buoyancy, elegance, humour

and slight provocation, occasionally employing banalities and trivialities. His linkage to

Classicism and inspiration by Bohuslav Martinů’s compositional techniques, as well as the

jazz influence and original application of the Latin meter, form a singular synthesis.

OBSESSION WITH LATIN

Motto:

“Accordingly, with great pleasure I make use of this living language, more immortal than

dead, for composing.” (J. Novák in the preface to Ioci vernales)

Novák’s great fondness for the language of Ancient Rome began in the first half of the 1950s,

when studying Latin became his main hobby and passion. The composer did not perceive

Latin, which he brilliantly mastered in both spoken and written form as a poet, as a dead

language but as a universal means of communication across the centuries.

He systematically cultivated his interest and in the 1950s founded in Brno a Latin club whose

members were only allowed to speak Latin. Novák’s creative approach was also reflected in

his conceiving words, enriching Latin with new expressions (he sought fitting equivalents for

“telephone’ and “refrigerator”, for instance).

His proximity to the spirit of Latin was recalled by the violinist Dušan Pandula: “And there

was always something mythological that he brought back to his everyday encounters with

Latin and antiquity; since Jan scolded his children in Latin, spoke Latin with his friends, and

used the language in telephone conversations with those who were at least a little bit on the

same wave length. He conducted endless discussions with the ‘devotees’ in Latin, and he

translated everything that got into his hands into Latin, The Good Soldier Švejk, for instance.”

VOCAL COMPOSITIONS

Novák’s vocal pieces to Latin texts are settings of works by Ancient Roman poets and prose

writers, medieval, Renaissance, as well as modern, authors, and largely his own texts. He

made proficient use of the possibilities of the given metre’s rhythm and worked with them in

an original manner for the sake of underlining the text’s meaning. The Latin metre also had a

vital impact on his thinking when composing solely instrumental works, in some cases he put

Latin verses ad libitum.

Evidently the very first composition setting Novák’s own Latin text was Exercitia

mythologica for mixed chorus, dating from 1968. The cycle, whose heroes are Antique

mythological figures, consists of eight choruses of a madrigal texture whose metric pulse is

based on quantitative meters.

Novák wrote the highest number of vocal pieces in Italy, where in 1971 he established the

Voces Latinae choir (the cycle Invitatio Pastorum, the song cycle Schola cantans, the opera

Dulcitius, etc.). Under his guidance, the ensemble started to perform almost exclusively non-

liturgical choruses to Latin texts in the classical Latin pronunciation.

In one of his letters to Brno, Novák wrote in this regard: “As I have written to you, at an

advanced age I had to set up a choir, even though I have no conducting ambitions whatsoever,

but necessity is the mother of invention. (…) I am cultivating with them Latin pronunciation,

since Latin phonetics has been neglected for some sixteen centuries. So I attend to the

education of the European people…”

After moving to Germany, Novák composed to Latin texts the ballet Aesopia for four-part

mixed chorus and two pianos or small orchestra (1981), based on “The Fables of Phaedrus”.

The most comprehensive collection of his Latin songs is the Cantica Latina for voice and

piano, published posthumously.

TRIBUTE TO THE COMPOSER

At the 24 May concert within the Prague Spring festival, Martinů Voices with the choir

master Lukáš Vasilek will present two Novák cycles that represent his crowning works in this

genre.

The extremely difficult to perform Fugae Vergilianae (1974) for mixed chorus is probably

Novák’s most notable Virgil-based composition yet has never been sung in its entirety on

a concert stage. Some 40 years after its origination, Prague Spring will be giving its world

premiere. All the piece’s sections play with the meaning of the word “fugue”, which is

derived from the Latin “fuga” (act of fleeing). The contrapuntal tissue of voices is thus

thematically linked by the motif of flight, be it departure from the homeland or the rush of

transient time.

The setting of the satirical last will and testament by Novák’s contemporary, the German

writer and Latin poet Josef Eberle (1901–1986), in the chorus Testamentum (1966) is

characterised by the unusual application of four horns (in Ancient Rome they were the

traditional instruments for mourning music) and imaginative twists of the tempo, rhythm,

expression and dynamics, respecting the satirical nature and development of the text. Pungent

humour gives way to the solemn tone in the poet’s will: “May the world not be as I used to

know it, may a person to a person not be like a wolf to a sheep.”

The selection of Novák’s choral works will be rounded off at the concert by the chamber

piece Sonata super Hoson zes (1981), which quotes the allegedly oldest preserved notation of

Greek music, “The Song of Seikilos”. It is one of the few works in which Novák was inspired

by Ancient Greek music. The sonata will be performed by the composer’s daughters, the

flautist Clara Nováková and the pianist Dora Novák-Wilmington.

The concert will be symbolically supplemented by the Czech Madrigals by Bohuslav Martinů,

who remained one of Jan Novák’s major models throughout his life.

| Composer | Composition | Creation year |

|---|---|---|

| Novák, Jan | Symphonia Bipartita | 1983 |

| Novák, Jan | Mimus magicus | 1969 |

| Novák, Jan | Ludi Symphoniaci | 1978 |

| Novák, Jan | Vernalis Temporis Symphonia | 1982 |

| Novák, Jan | Variations on a Theme of Bohuslav Martinu | 1949 |

| Novák, Jan | Sonata da chiesa II for flute and organ | 1981 |

| Novák, Jan | Sonata super | 1981 |